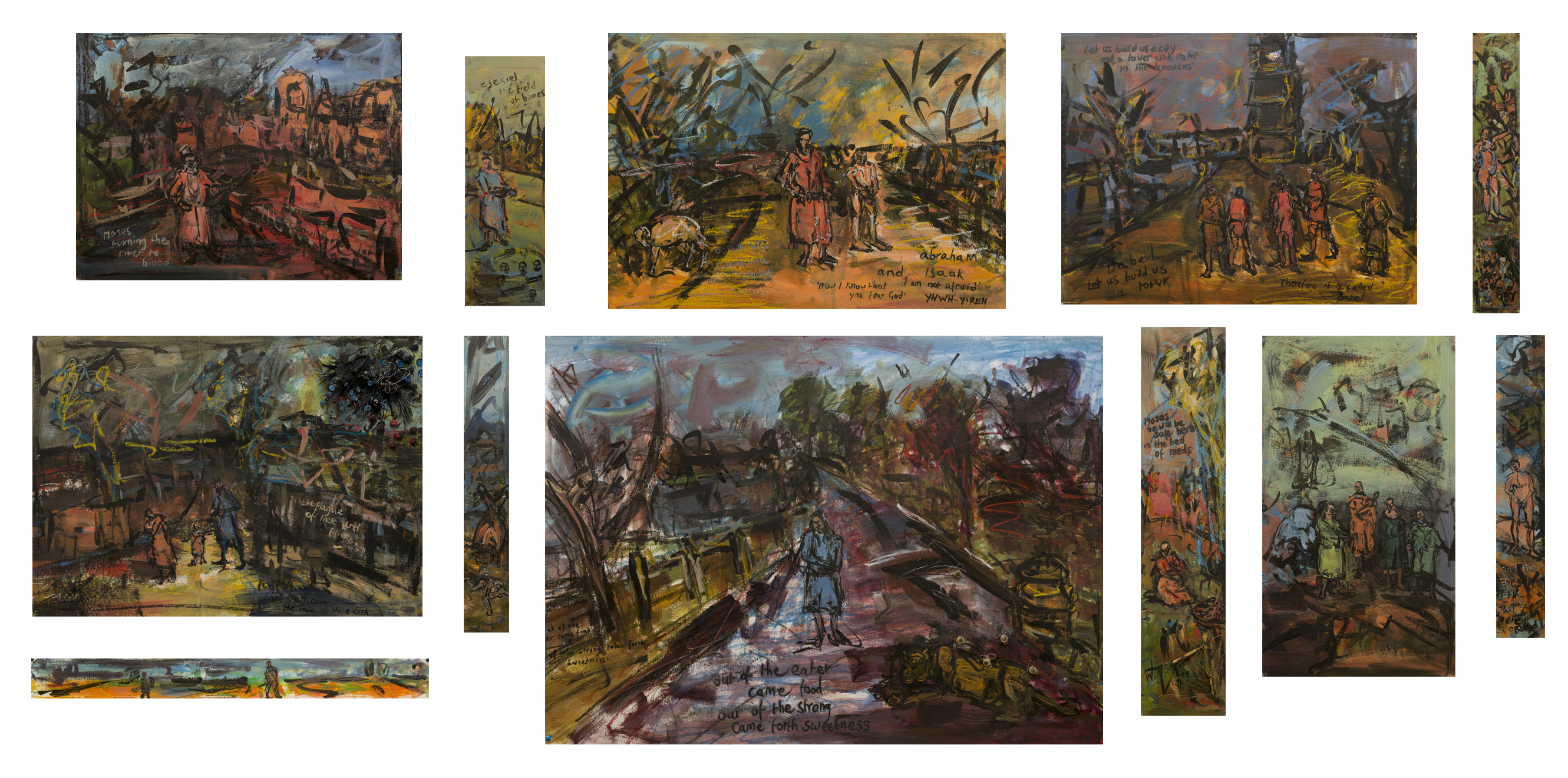

Old Testament 2016

A series of twelve mixed media paintings depicting stories from the Old Testament. These paintings can be joined to form a contemporary altarpiece or shown individually.

It is currently being shown at St. Martin's Church Gospel Oak, London.

Artist’s introduction to the work

Van Gogh famously referred to painting as a 'small light in a dark world.' Using a combination of gouache, oil pastel and collage, I have tried to illuminate this selection of Old Testament narratives in order to evoke the initial emotional response that I had to these stories when I first encountered them as a child at school

In practical terms, what you see is the culmination of a process that began with the depiction of one image, Samson and the Lion. Through that early painting I found I could tell the story using an imaginative and novel technique- a combination of paint, oil pastel and collage.

Through colour and luminosity I wanted to express the spiritual aspect of the work and felt that this would be particularly effective in an ecclesiastical setting. The energetic use of line injects a tension, and delivers an electrical charge to the whole. It should also suggest an outside force, a charge or impulse that goes through all living things emanating from the Almighty; in the Old Testament context an 'admonishing force'.

The three-dimensional nature of collage generates a physical aversion to the plague of lice and flies. It is as if past horrors are projected into the present, forcing the onlooker to interact with the work and subject matter in real time.

Click and scroll image for large view.

About the work: by Philip Stoltzfus, Art Collector

I met Helen 12 years ago, shortly after she had completed a hugely ambitious cycle of collages around Milton’s “Paradise Lost”. My mother had died 6 months earlier, leaving me with a numbing, grinding grief, so perhaps I was ready for an immersion into this world of chaos, darkness and light, into Helen’s palette of melancholy blues and sinister reds punctuated by earth tones, the latter a haven from the surrounding tumult. The pictures were dark and a little frightening, but within them there seemed an empathy, an appeal to humanness, that I deeply needed at the time.

Since then I have seen every stage of her work, her successes and failures (amazing to imagine someone simply painting over a project of nearly a year, and starting again), and have become accustomed to the brooding quality of her art, a place where tragedy seems nearly certain and kept at bay by sheer will and empathy. This is not to suggest Helen’s work is narrative – it is not in the slightest; rather it conveys itself through expressionistic power and colour, a kind of visual music, “the force that through the green fuse drives the flower”.

So now Helen has turned her hand to the Old Testament, a suitable test of expressionist values, allowing her to draw from her (sometimes tempestuous) Catholic upbringing as well as her familiarity with the religious pictorial language of so much of the art of the past. There is no theology to these paintings. They are the half recalled stories of childhood churchgoing, broken shards of memory, the sub-structure of our collective mythology that has formed Western culture and art and psychology, the part we still have left to hang on to with faith’s “melancholy, long, withdrawing roar”.

Who can explain these strange stories? A man is willing to execute his son in response to internal voices, another is swallowed whole by a fish who vomits him out at the place of his destiny, a baby is found in the weeds of a river bank, raised by Pharaoh’s daughter and then leads a remarkably reluctant nation to escape Egyptian bondage. A strong man slays a lion whose carcass produces a colony of honey bees; he kills a thousand men with the jawbone of an ass and attaches torches to the tails of foxes to burn his enemies’ fields. It is a world of pestilence and rivers of blood, nearly casual miracles, hubris meeting nemesis, and a prevailing sense that it all could have been much better had two young people not succumbed to the advice of a wily serpent. Perhaps it is the vividness and strangeness of these tales that explains their enduring grip on our post-religious consciousness.

Do not, therefore, look for thematic connections between these pictures; they are images assembled like the repair of a stained glass window of a church exploded in a WWII bombing raid. And for all the darkness of Moses turning the Nile to blood, there is a lightness of touch here and a humour that captures the nostalgia of these stories – for sure, there is a terrible plague, but in the end it is a plague of buttons and contorted wires, Samson’s lion has the insouciance of Durer’s version with Saint Jerome, while bees buzz merrily down a lane, Eve remains quite brazen while Adam is abashed, and David meets Goliath in a Tuscan landscape in the glow of the first mornings of the first days. While there remain hints of the melancholy blues, the colours are light, even joyful, and yes, one can look and look again, finding new detail, new connections, and feel something close to gladness.